Adaptive re-use of an historic church structure

Canadian Property Valuation Magazine

Search the Library Online

Adaptive re-use of an historic church structure

*Adapted from a presentation made by Giovanni Geremia, maa, oaa, aaa, saa, mraic at the Appraisal Institute of Canada 2016 Annual Conference in Winnipeg

“When we build, let us think that we build forever. Let it not be for present delight, nor for present use alone. Let it be such work as our descendants will thank us for; and let us think, as we lay stone on stone, that a time is to come when those stones will be held sacred because our hands have touched time, and that men will say, as they look upon the labour and wrought substance of them, ‘See! This, our fathers did for us.’”

– John Ruskin, a leading English art critic of the Victorian era,

Background

Preserving landmark buildings is an honorable objective in this day and age where the mantra is too often “out with the old and in with the new.” Unfortunately, such honorable objectives are not always achievable when practicality and feasibility come into play. Is there a practical use for the structure? Is the expertise available to make any kind of re-use a reality? Are there enough financial resources to complete a re-use project and ensure its ongoing feasibility?

In the case of Winnipeg’s landmark building known as the First Church of Christ, Scientist, completed in 1916, the answer to all of these questions was a resounding ‘yes!”

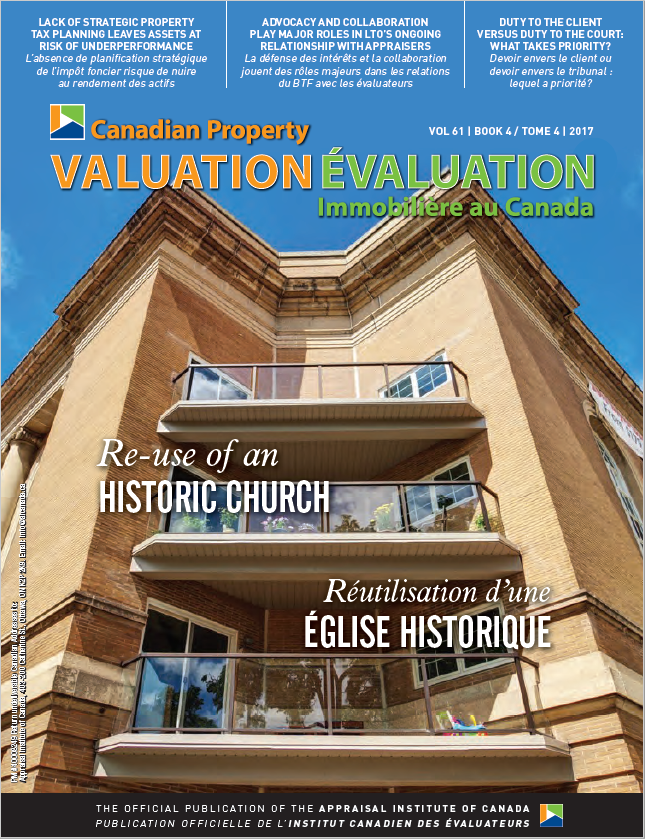

Located at 511 River Road in Winnipeg’s Osborne Village, original construction of the building began in 1910 with the basement and main floor. It was completed in 1916 when an auditorium was added above the original structure. The building plan took the shape of a Greek cross with its equally sized and aesthetically similar facades displaying a Beaux-Arts classical style. A fixture in the community for decades, as the 21st Century arrived, like countless other landmark buildings, diminishing use and resources made for an uncertain future.

By 2008, the building had actually been empty for several years. The previous owners had attempted to convert it into condominiums, but the economic viability of the project did not appear to work. When the owners applied for demolition, the fate of the building was brought into public discussion.

Putting the pieces together

To the rescue came Giovanni Geremia and business partner Brian Wall of the architectural firm gw architecture inc. Combining their familiarity of the building and the neighborhood with their sense of creativity and perseverance, their first priority was to ensure that the economics of the project made sense and to find people who were willing to take a chance on its future. After presenting their ideas to Kurtis Sawatzky, president of Stonebridge Development Group Ltd., who also knew and loved the building, the purchase was completed by Stonebridge in 2008. With the selection of G&E Homes as the contractor, the project now known as Studio 511 became a reality.

According to Giovanni, “Great care and effort went into building this structure and we felt strongly that it should not be dismissed as useless because of its age and the fact that it had lost its original reason for being. We believe that historic buildings are important because they provide a window on our past as a society, as a community and as individuals. Their presence reminds us of our history, the story of how we got to where we are today and what shaped us. As soon as a building disappears, all the connections and memories associated with it disappear.”

Both Giovanni and Brian believed that a second important reason for putting old historic buildings to new use was for the sake of the environment. Since a key rule to sustainable development is to reduce, re-use and recycle, they believed that philosophy should be applied to buildings as well as to everyday items like beverage cans. If a structure is in good shape for re-use, why not do so? Why not use some creativity and collective talents to find a new way for a building to continue serving society.

The re-use concept

The concept for the adaptive re-use of the church was to turn the building into condominium units that were designed and sized for the unique demographics of the Osborne Village community. To make the project viable, a maximum number of units were necessary, which resulted in final plans providing for 46 one-bedroom units. With local demographics indicating that significant numbers of young professionals and seniors lived in the area, either as singles or couples, the size of the units ranged from 500 square feet to 900 square feet, with pricing set so that monthly mortgage payments were similar to rents in nearby facilities.

Public consultation

Since the building was important to the fabric of the neighborhood, residents wanted as much of it preserved as possible. To achieve this objective, gw spent three months meeting with stakeholders and city officials, as well as staging an open house to provide information and gather input. This process of public consultation and involving city officials in the planning of the project paid dividends later on when the zoning variance hearing became a simple formality.

“In proposing changes to existing historic structures or new developments, it is very important to begin discussions with all stakeholders early on in the process,” says Giovanni. “Building consensus before plans are finalized is vital to the success of a project.”

Zoning challenge

The greatest challenge from a zoning perspective involved the parking that was available to residents. The site is restricted in its overall space and there were only 21 parking stalls for the 46 units. The City of Winnipeg required a total of 55 parking stalls. To overcome this obstacle, an innovative solution was negotiated with the Zoning Department whereby the developers provided three car-share vehicles as part of the development agreement. These cars would be used and managed by the residents. It was also determined that only 50% of the people in the area used vehicles for work, opting instead to walk, ride bikes or use one of the eight bus routes in the area.

Planning considerations

Unfortunately, in order to save the building, its remarkable interior basically had to be demolished. Attempts were made to save the organ screen and reuse it in the lobby, but the plaster was brittle and suspected of containing hazardous materials. There was only one floor in the church’s existing building, however, because it had a slope it could not fit the new layout. In essence, the existing building became a shell within which to build the new five-storey structure.

While the interior had to go, the exterior fared considerably better. In order to maintain the exterior of the building as much as possible, the planning of the units revolved around existing elements. The central units were long and narrow so that they would fit between the building’s long arched windows. This also kept the framing element sizes minimal due to short spans. The punching out of windows and doors for the corner units took place mainly in the recessed corners of the structure in order to maintain the exterior building massing. Balconies were also provided for the corner units. Five floors were built within the structure, however, since code restrictions allowed for only four floors of combustible construction plus a mezzanine, only a portion of the fifth floor was used as loft space. The remainder of the fifth floor’s unusable and inaccessible space allowed for finishes to be left intact as a ‘record’ of the original plasterwork and details.

“There are always ‘surprises’ when working with existing buildings,” says Giovanni, “but familiarity with a particular historic structure and early evaluations of all possible issues that may arise go a long way in mitigating problems that could arise during construction. In this case, we did not run into any major unforeseen problems during the construction.”

A great end result

After four years of caring, meticulous work, Studio 511 was completed and opened for business in 2013. In 2014, the project received the Heritage Winnipeg Special President’s Award for Preservation of a Neighborhood Landmark. According to Giovanni, all of the time and effort put into the project was more than worthwhile. “The feeling that came with seeing residents going into and out of the building for the first time was indescribable,” he says, “as was the satisfaction we got from knowing that our company initiated and played a major role in giving this 100-year old building a purpose once again.”

With prices set at levels where the mortgage payments were similar to monthly rents in the area, the units sold well and only a handful remained available after completion of the project. All units were sold very quickly once the project was completed and four years later very few appear for resale. If and when a unit does come up for sale, the pricing is certainly higher than the original sale price.

Summary

In order for a project to be successful, the economics have to work for the proponents who are willing to take on the risks in redeveloping or adaptively re-using older historic structures. Just as important to the success of a project such as this is creativity, knowledge of the structure and an understanding of how to maximize its potential.

Unfortunately, there will be times when sacrifices to the original intended use and some of the historic elements become necessary in order to save and re-use buildings that appear no longer viable in the role for which they were originally designed and built. “Decisions to remove historic structures are often made too quickly without looking at all the possibilities,” says Giovanni.

511 River was originally built as a gathering place for people of the same faith. Today, its role has changed, but it still brings together a community of like-minded people who choose to live in the vibrant neighbourhood of Osborne Village. Even with all the changes, the building’s historic importance to the fabric of the community carries on.

-30-