Collateral damage: a brief history and the effects of housing discrimination in Canada

Canadian Property Valuation Magazine

Search the Library Online

EQUITY, DIVERSITY AND INCLUSION (EDI)

Collateral damage: a brief history and the effects of housing discrimination in Canada

“The greatest challenge of our times is not better technology; it is defeating prejudice in all its forms.”

– Simon Ives

Institutional discrimination: housing and mortgage lending

Discrimination is defined as the unequal treatment of different groups of people. Most of us think of discrimination as a set of specific actions such as using racial slurs or refusing to do business with certain types of people. However, a greater blight that often goes unnoticed is institutional prejudice. Institutional prejudice and discrimination are the biases that are built into the operation of society’s institutions like schools, housing, banking systems, and the workforce. The concept of institutional racism was first highlighted by civil rights activists Stokely Carmichael and Charles Hamilton in the 1960s. They argued that institutional racism was harder to identify and, therefore, less often condemned by society.

This is supported by a 2022 report conducted by the University of Toronto’s Centre for Urban and Community Studies for CMHC (Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation) entitled Housing Discrimination in Canada: What we know about it. This report highlighted the lack of research in mortgage lending in Canada. There is no new Canadian research on discrimination in mortgage lending, though that does not mean that it does not occur. In the US, studies suggest that black homeowners are denied home mortgage loans at a higher rate than their white counterparts, even when the black and white applicants have similar qualifications related to income, credit records and other eligible characteristics. Given that some facets of the Canadian financial sector are similar to its southern neighbour, it is safe to assume that we have similar problems in our system, albeit perhaps on a smaller scale.

The gap increases among marginal applicants (those with less-than-ideal credit records) according to the applicant’s race or sex. Additionally, US studies indicate that women and visible minorities may be discouraged from applying for a mortgage in the first place.

Little information is available on discriminatory practices in mortgage lending in Canada.

Research in Canada

Anecdotal evidence suggests that such discrimination exists in Canada, but no studies have been done to confirm this. In Canada, banks do not provide material information about their lending policies, therefore, there is no public accountability in this area. Also, Canadian banks do not maintain records that track successful and unsuccessful mortgage applicants or the criteria that were utilized to determine the success or failure of these applications.

The research available suggests that housing discrimination exists in Canada. The existing studies are small scale, limited to a few cities, and nearly all have focused on the rental sector and on racial discrimination. Little systematic research is available on the homeownership sector or other forms of discrimination.

The study also suggests that systematic research is critically needed, in the following areas:

- housing audit studies (especially paired testing) in major cities, focusing on blacks, Aboriginals, female-headed households, families with children, youth, people with physical disabilities, and low-income households;

- surveys of perceived discrimination and its effects on home-seeking behaviour and outcomes in both large and small urban centres;

- surveys on the housing experiences of specific ethnic groups in specific cities.

Studying mortgage lending practices is more difficult, because of the privacy of transactions. However, exploratory research involving surveys of the general population and mortgage holders might indicate the nature and extent of discrimination in this area.

CMHC research 2021

At the end of 2021, CMHC released its first report entitled Homeownership Rate Varies Significantly by Race. The new report highlighted many inequities among various racial groups. Between 2011 (National Health Service – NHS) and 2016 (Census), the overall homeownership rate fell by 2.74 percentage points. The biggest proportional drops in homeownership rates came from the Black, Filipino, Arab, West Asian, and Korean groups. According to the 2018 Canadian Housing Survey, nearly three-quarters (73%) of the population lived in a dwelling that was owned by a member of the household. Seniors (78%), South Asian people (74%) and veterans (73%) lived in owner households at similar rates as the population as a whole, while Chinese people (85%) were more likely to live in owned dwellings. This was not the case for the Black population (48%) and recent immigrants (44%), where less than half of these population groups lived in owner households and were more likely to rent. In summary, the homeownership gap between these racial groups and other racial groups increased between 2011 and 2016. Similar racial group differences exist when evaluating the change between the 2006 and 2016 censuses, with the notable exception of the Aboriginal peoples and Latin American groups that demonstrated positive growth between 2006 and 2016.

A chapter in the history of housing discrimination in Canada – Africville

Africville was a primarily Black community located on the south shore of the Bedford Basin, on the outskirts of Halifax. The first records of a Black presence in Africville date back to 1848, and it continued to exist for 150 years after that. Over that time, hundreds of individuals and families lived there and built a thriving, close-knit community. There were stores, a school, a post office, and a church. Nearly a hundred years later, in the 1960s, many residents of Africville still did not have running water or even a sewage system[i].

Unfortunately, discrimination and poverty presented many challenges for the community of people in Africville. The City of Halifax refused to provide many amenities other Haligonians took for granted, such as sewage, access to clean water, and garbage disposal. Africville residents, who paid taxes and took pride in their homes, asked the city to provide these basic services on numerous occasions, but no action was taken. The City compounded the problem by building many undesirable developments in and around Africville, including a fertilizer plant, slaughterhouses, Rockhead Prison (1854), the ‘night-soil disposal pits’ (human waste), and the Infectious Diseases Hospital (1870s). In 1915, Halifax City Council declared that Africville “will always be an industrial district”[ii]. While dealing with small land allotments, the people of Africville were already at a disadvantage and the health hazards bought in by the city devalued the area even more, thus restricting the ability of Africvillians to build wealth through homeownership.

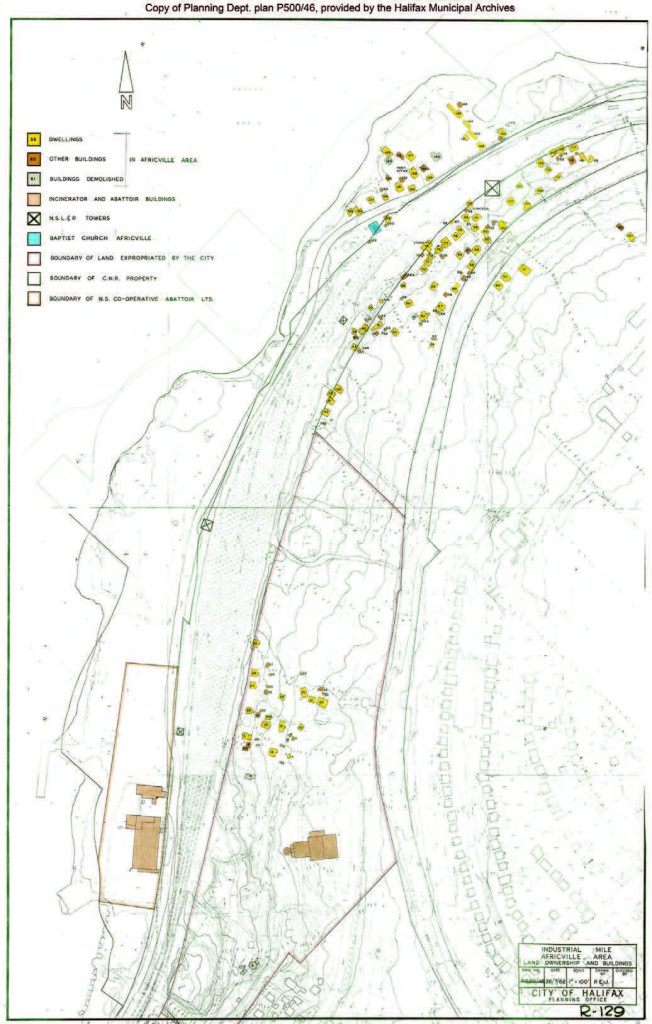

Copy of Planning Department provided by the Halifax Municipal Archives – Africville Map 1962

(https://www.halifax.ca/about-halifax/municipal-archives/source-guides/africville-sources)

In 1964, the City of Halifax authorized the relocation of Africville and offered payments for homes to people with deeds. Those without deeds, irrespective of the time they owned the properties were offered $500. In most of these cases, the homes had been built, owned and lived in for generations. By 1970, the last home in Africville was destroyed.

After the relocation, displaced residents found that the ‘home for a home’ deals did not materialize. Many realized that the monies paid for their land and property was only enough for a down payment on a new home or a short period of rental in public housing. To make matters worse, the City of Halifax dismantled the support structures intended to assist former residents only three years after relocation began. Those who stayed in Halifax felt forced to turn toward welfare to cover the rising costs of living in the city. Many left the city and moved to other parts of the country. This has affected the generational wealth of all the residents and subsequent generations of Africville and has kept homeownership low for racially marginalized communities and groups.

Reparations for the disenfranchised: repairing lasting damage

Chicago (Evanston) became the first US city to offer reparations to black resident families who suffered damage from decades of discriminatory and segregationist policies, the most prominent of which was redlining.

In March 2021, it was announced that an amount of $25,000 per eligible household would be granted for home repairs, mortgage assistance or mortgage down payments. The housing grants are more narrowly targeted to residents who can show that they or their ancestors were victims of redlining and other discriminatory 20th-century housing practices in the city that limited the neighbourhoods where Black people could live. Eligible applicants could be descendants of an Evanston resident who lived in the city between 1919 and 1969, or they could have experienced housing discrimination because of city policies after 1969.

This step by Chicago (Evanston) sets a precedent for future reparations and will help model what could be an improved future for all injured parties. At least, that remains the hope.

The practicality of implementing reparation programs, especially on a large (national scale), is still a hot topic of discussion and dialogue across both Canada and the US.

References and Bibliography

- http://www.urbancentre.utoronto.ca/pdfs/researchbulletins/11.pdf

- https://journals.lib.unb.ca/index.php/acadiensis/article/view/18419/19899

- https://www.halifax.ca/about–halifax/municipal–archives/source–guides/africville–sources

- https://www.cmhc–schl.gc.ca/en/professionals/housing–markets–data–and–research/housingresearch/research–reports/housing–finance/research–insight–homeownership–rate–varies–significantlyrace?utm_medium=email&utm_source=eblast&utm_campaign=housing–research&utm_content=english

- https://www.koho.ca/learn/redlining–in–canada/

- https://www.brookings.edu/research/americas–formerly–redlines–areas–changed–so–must–solutions/

- https://www.npr.org/sections/health–shots/2020/11/19/911909187/in–u–s–cities–the–health–effects–of–pasthousing–discrimination–are–plain–to–see

- https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/46–28–0001/462800012021001–eng.htm

- https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/daily–quotidien/211122/dq211122b–eng.htm

- https://youtu.be/HAn1RbPGynY

- https://globalnews.ca/news/7725225/chicago–suburb–evanston–black–reparations/

- https://www.ted.com/talks/simon_ives_defeating_prejudice?utm_source=tedcomshare&utm_medium

End notes

[i] Canadian Museum for Human Rights: https://humanrights.ca/story/the-story-of-africville

[ii] Africville: A Story of Environmental Racism: